STATE OF THE ART: The Qur'anic manuscript

From a material standpoint, the Qur’an is both the first book of the Islamic world and the most representative object of the Muslim community’s identity. Its production requires significant human and economic investment, involving a complex manufacturing process and the participation of various art and craftsmanships : parchment makers, copyists, illuminators, binders… Each manuscript captivates us with its beauty and history; and its testimony is extremely valuable because, in a situation rarely seen in the history of Late Antiquity texts, some manuscripts could date back to a time close to the very composition of the Qur’an, estimated to be approximately between half a century and a century.

Over the centuries, the Qur’anic book (muṣḥaf, pl. maṣaḥif, in Arabic) both accompanies and reflects the progressive construction of the new empire and new Islamic identities. Indeed, the vast Islamic expanse, stretching from Andalusia to India, gradually gives rise to a plurality of scribal traditions. Each tradition distinguishes itself through its own interpretation of writing styles, the shape of the book, its decoration, or the presentation of the Qur’anic text itself. Over time, these particularities evolve: new color pigments or new writing materials are sometimes discovered. Additionally, certain calligraphic styles or decorative motifs may fall into oblivion, while others persist or reemerge in another part of the Islamic world, thus demonstrating the circulation of books and people.

The history of the manuscript transmission of the Quran over time is difficult to reconstruct. After centuries of preservation and transmission, the manuscripts that have reached us have mostly become anonymous. Often, they no longer contain information regarding the date, place of production, or patron. They are also often so damaged that the binding has disappeared and the leaves have been separated and scattered by merchants or collectors. It also happens that ancient scripts were imitated for restoration purposes – to replace lost leaves – but also to deceive and take advantage of collectors. Thus, we no longer know the context in which the leaf or manuscript was produced and transmitted, nor what it originally looked like. However, if one takes the time and trouble to gather the fragments of a dispersed manuscript and examine them closely, it is possible to outline its production context and subsequent travels.

Here is a brief introduction to the different elements that make up the Quranic manuscript and their variations. These variations emerge over time, depending on geographical location, as well as socio-economic and political reasons.

The different script styles

The history of writing is a dynamic narrative of graphical manifestations that must be deciphered by the paleographer, dated, and localized. The paleographer adopts two approaches. One is synchronic: by observing the handwriting used, they seek to understand the date, place of creation of an artifact, as well as how the scribe organized their copying work. The other approach is diachronic: it must reconstruct the process of transformation of individual signs and the overall graphic system.

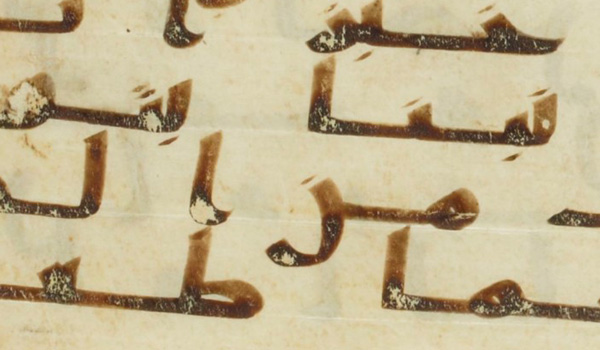

From the origins until approximately the 11th century CE, two main varieties of Qur’anic handwriting are known. The ḥijāzī – a term coined in the 20th century from the expressions “script of Mecca” and “script of Medina,” used in Ibn al-Nadim’s fihrist, an Arabic text from the 10th century – is characterized by a sometimes rounded ductus and a slanting of the stems to the right. It is distinct from the other variety of script style gathering a vast group of angular and vertical scripts, commonly referred to as kūfī.

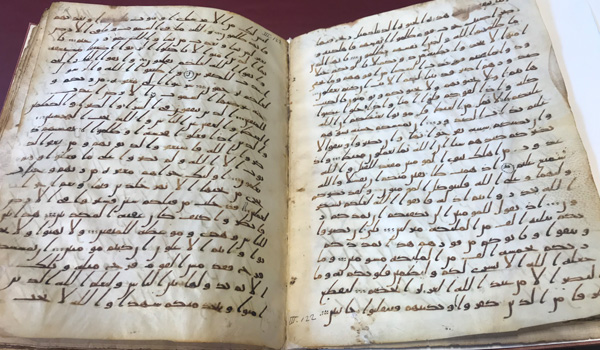

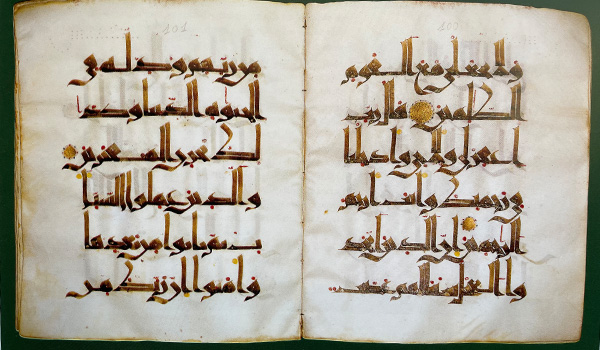

ḥijāzī style (Paris, BnF Arabe 328)

ḥijāzī style (Paris, BnF Arabe 328)

These designations pose several problems. Firstly, they outline a relatively precise geography of scripts, while no material evidence currently supports this geography. We have no certainty that they correspond to the region where the style was invented, nor even to the places of manuscript production. Furthermore, they do not reflect the immense stylistic diversity within these sets, especially within kūfī. The challenge of classifying the vast kūfī was only faced from the 1980s, with the work of François Déroche, who preferred the term “ancient Abbasid scripts,” bringing together seven main styles, designated by letters from A to F; as well as O (corresponding to Umayyad). Within these styles, several series are isolated (indicated by Roman numerals), primarily based on their general characteristics, and to a lesser extent on the specific stroke of certain letters. Finally, some series still exhibit a slight slant of the vertical strokes (between 80 and 95° for alif and lām), which are considered in defining the subseries (B.I a, O.I a, or C.I a).

Around the 9th century CE, alongside kūfī, a new style began to be employed for copying the Qur’an. This style is a blend of kūfī and scripts used for secular book copying (bookish scripts), now designated by the name “New Style” or also Broken Kūfī, or Eastern Kufic. Once again, this geographical reference does not align with the reality of manuscripts, several of which were copied in the Western Islamic world. To cite just one example, the “Nurse’s Qur’an” was copied in Kairouan in 410/1020.

The “New Style” in the “Nurse’s Qur’an” (Mushaf al-Hadina), Metropolitan Museum 2007.191

Alongside the use of this style, which is also subdivided into several subfamilies, other styles emerge on a regional scale. In North Africa and Andalusia, the Maghribi style develops, which can be found in Qur’anic manuscripts from North Africa and Andalusia as early as the 11th century CE. This script has stylistic variations depending on regions and periods. It also influences certain varieties of scripts in West Africa, such as Sahrawi (Saharan script), belonging to the vast group of African scripts known as Sūdānī, for which a more precise classification is currently being developed.

The Maghribi style (Metropolitan Museum 42.63)

In the East of the empire, rounder scripts begin to be used for copying the Qur’an. These are referred to as the Six Pens. Among these styles, the Naskh is used for the text of the muṣḥaf of Ibn al-Bawwab written in Baghdad in 391/1000-1, while illumination employs Thuluth (literally 1/3) for the titles. Another style among the Six that will gain great prominence is Muḥaqqaq, widely used to copy Qur’anic manuscripts of the Mamluk sultans of Egypt and the Ilkhanid sultans of Iran.

At the borders of the empire, these round scripts themselves give rise to local styles: for example, Bihari is a variety of naskh, used in India between the 14th and 16th centuries to copy high-quality Qur’anic manuscripts (Brac de la Perrière, L’art du livre dans l’Inde des sultanats). Bihari’s reputation is such that its influences can be found as far as in manuscripts made in Yemen and East Africa. Another example is in China, where since the 15th century, a style derived from Muhaqqaq, called Sini and marked by greater horizontality, has been used (Fraser,”Beyond the Taklamakan”).

Writing materials

Writing material

On what medium was the Qur’an originally written? The narratives of the Islamic tradition mention the use of makeshift media: pieces of leather, palm ribs, camel bone, stones, etc. There are no material traces left of this primitive period. But there is evidence from more recent times that these same materials were used for writing.

Legal archives on wooden sticks, Morocco, 19th-20th century

Legal archives on wooden sticks, Morocco, 19th-20th century

For the first centuries of Islam, the materials preserved reflect a fairly homogenous situation: with the exception of a few rare fragments on papyrus, the earliest Qur’anic books known to us today are almost all written on parchment. Like leather, parchment was made from animal skins – usually domestic (sheep, goat), although there are many Arabic catalogues mentioning Qur’an manuscripts on gazelle skins. The tradition of copying on parchment continued in some western regions of the empire until around the 14th century CE. In the East, however, paper replaced parchment fairly soon afterwards. The first Qur’anic manuscripts on paper are attested from the 10th century onwards and come from Iran.

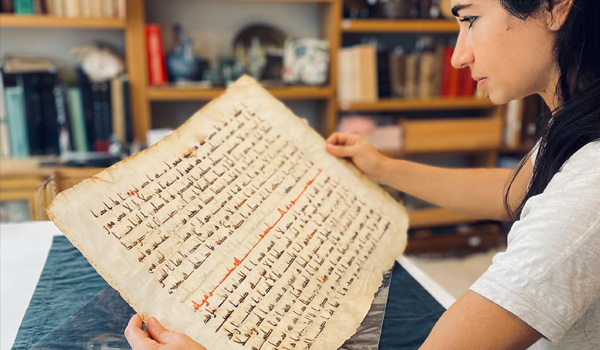

Manuscript on parchment – 12th or 13th century – North Africa

Manuscript on parchment – 12th or 13th century – North Africa

Whether it was parchment or paper, craftsmen explored a wide range of techniques to obtain better quality materials, combining this with a constant quest for aesthetic perfection. So we find parchment and paper of varying thicknesses, depending on the region and the period, but also parchment painted in blue and paper coloured or silhouetted with gold powder…

Inks and pigments

In Qur’anic manuscripts, black ink is traditionally the first choice for writing the Sacred Text. There are several categories of black ink, the two main ones being carbon-based inks such as soot or charcoal, and metal gall inks. It is possible to identify the nature of the ink and assess its homogeneity in a manuscript using non-invasive physico-chemical analysis methods. Several analysis campaigns carried out on ancient manuscripts have made it possible to identify the inks used in the oldest manuscripts of the Qur’an. The inks used were always metal gall inks, generally made from metallic salts – iron oxide in particular, but also copper – mixed with a natural tannic substance and a binder.

Manufacture of metal gall ink

Manufacture of metal gall ink

Colour has been introduced sparingly to highlight textual transitions: the passage between two surahs, separations between groups of verses, etc., but also to mark vocalisation. As these components are not part of the original text, people used a colour other than black to distinguish them. Red is the colour most commonly used for these purposes, but many other coloured pigments have been employed depending on the period and the place of production and circulation of the manuscripts.

The making of a book

The physical presentation of the Qur’anic book has responded to multiple challenges over the centuries, as well as according to regions and the social environment in which the manuscript was produced.

These challenges are visible through the manufacturing of the book itself and its variations.

Formats and orientations of the book

Throughout history, various manuscripts of different dimensions have been produced. In the early times, on parchment, there exist monumental books – such as the muṣḥaf attributed to Caliph ‘Uthmān ibn ‘Affān (reigned between 644 and 656 CE), preserved in Cairo (Sayyida Zaynab Mosque, Central Library) – and miniature books like the muṣḥaf which, according to its colophon, was commissioned by Caliph Harun al-Rashid in 182 AH / 799 CE and offered to Charlemagne (Paris, BnF Arabic 399).

Later, the use of paper allows for surpassing the limits imposed by animal skin and producing sheets up to two meters in height and one meter in width – such as the muṣḥaf attributed to Prince Baysunghur (d. 1433), grandson of Genghis Khan. Conversely, miniature books became smaller and smaller.

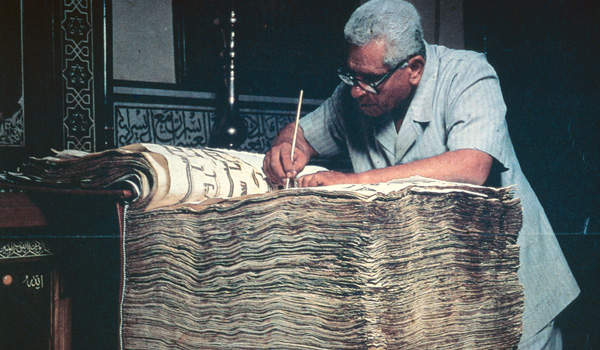

Muṣḥaf attributed to Caliph ‘Uthmān ibn ‘Affān (Cairo, Sayyida Zaynab Mosque, Central Library)

Muṣḥaf attributed to Caliph ‘Uthmān ibn ‘Affān (Cairo, Sayyida Zaynab Mosque, Central Library)

The format also concerns the orientation of the book: vertical, horizontal, and sometimes square books were produced.

In the early centuries of Islam, the Qur’anic book copied in kūfī script is predominantly associated with horizontal formats – also called landscape format, similar to our landscape orientation. Various interpretations have been proposed regarding the use of these different orientations (see my article “Consonantal dotting in early Qur’anic manuscripts: A fully dotted Qur’an fragment from the AH. 1st/AD. 7th century”).

Qur’anic folio from the 8th century in oblong format

Qur’anic folio from the 8th century in oblong format

The construction of the quires

Let’s start with a brief definition! A book is made up of several quires, themselves made from several parchment or paper sheets that are stacked and folded in half (called bifolios). Once the quires are made, everything is bound together using a sewing thread. However, let’s keep in mind that this binding step is not systematic. The construction of the manuscript thus follows a logical and regular structure.

However, we can observe that, depending on the places and times, manuscripts do not adhere to a single manufacturing technique, neither in the number of sheets inside the quire (quires of 6, 8, or 10 sheets) nor – when it comes to parchment – in the way the parchment faces are arranged (juxtaposition or opposition of the flesh side and the hair side of the parchment). In Sub-Saharan regions, it is even impossible to speak of quires, as manuscripts regularly consist of isolated and non-sewn sheets.

The binding

The binding of a book is not only intended for aesthetic purposes, but also to preserve it, ensuring its longevity. Contemporary conservation efforts focus on the maintenance and restoration of these bindings, as they provide valuable information about historical book-making practices and cultural aesthetics.

Bookbinding techniques have evolved over time, influenced by cultural, artistic and technological advances. Only a few Qur’anic bindings from the first Islamic centuries exist, allowing us to identify two different types of binding.

Over time, these manuscripts were decorated with complex drawings, gold leaf or calligraphy in relief on the covers. As the art of bookbinding progressed, techniques such as tooling, filigree work and inlay were used to embellish the covers of the manuscripts.

Layouts

Rulings

The preparation of the page before writing is a fundamental phase that allows us to learn more about the scribe’s work, as well as the spatiotemporal context in which the copying took place. Ruling encompasses all these reference points and lines that help delineate the text area, the number of writing lines, and simply maintain straight and parallel lines among them.

Dry point ruling

Dry point ruling

To achieve this, various tools are available: the dry point is a kind of stylus that, through pressure, creates a relief on the sheet, or even multiple sheets at once. One can also trace ruling with ink or carbon. In this case, it can be easily erased, which may have happened in the case of many manuscripts in “classical” kūfī where no trace of ruling is visible, unless scribes employed other techniques. With the emergence of paper, a masṭara/misṭara (ruling board) is indeed used.

Illuminations

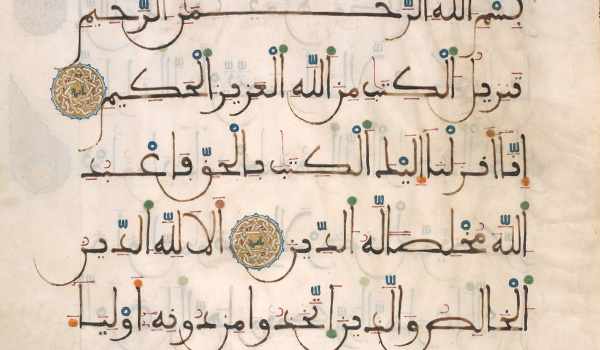

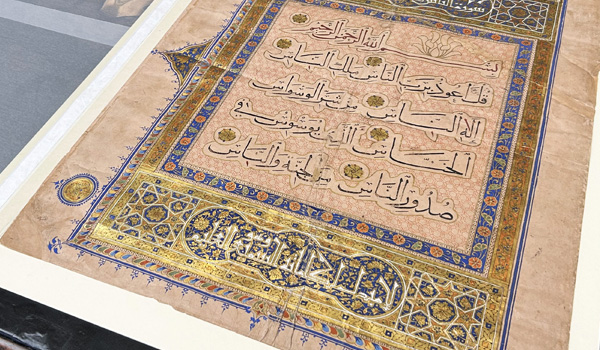

Qur’anic manuscripts often feature decorations placed at various locations within the text. Full-page decorations may precede the beginning of the text or a section and conclude its end. These same parts of the text usually receive more attention from the illuminator: the text is often framed within a more or less large border. Additionally, each transition between the surahs receives special treatment from the illuminator.

Muṣḥaf from the Mamluk dynasty, 15th century, V&A Museum MSL 1910.6099

Muṣḥaf from the Mamluk dynasty, 15th century, V&A Museum MSL 1910.6099

In the early centuries of Islam, four ways of separating the surahs in manuscripts are known: leaving a blank space, using decoration, employing a title formula with or without the verse count, and combining decoration with a title. In the mid-20th century, scholars G. Bergsträsser and A. Grohmann assumed that these presentations illustrated successive chronological phases.

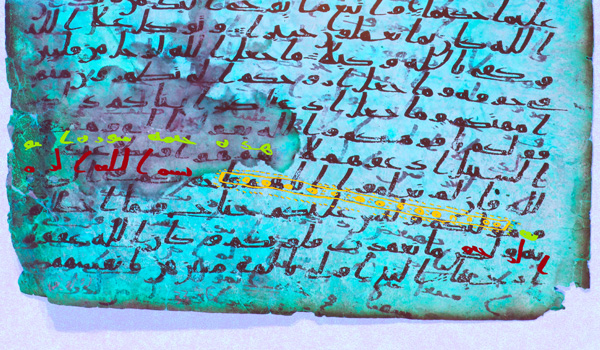

However, today, a better understanding of the material evidence leads us to revisit these hypotheses. The assumed chronological framework no longer matches with the evidence of ancient materials. For example, the lower layer (scriptio inferior) of the Ṣanʿāʾ palimpsest contains a surah title without a count, inserted within the text itself, thus proving the contemporaneity of the title and the text. Besides the title, there are ornaments that appear, at first glance, contemporary with the text. This example shows that by the end of the 7th century CE, several types of presentation were already known.

Surah’s title and ornament in the lower layer of the Ṣanʿāʾ palimpsest (Ṣanʿāʾ DAM 01-27.1)

Surah’s title and ornament in the lower layer of the Ṣanʿāʾ palimpsest (Ṣanʿāʾ DAM 01-27.1)

Subsequently, the addition of surah titles becomes systematic, but there are still variations in presentation – with or without ornamental bands – and even in the formula used. Sometimes the verse numbering is formulated differently, and the choice of the title varies.

Muṣḥaf attributed to the Umayyad caliph al-Walid I, (Ṣanʿāʾ DAM 20-33.1)

Muṣḥaf attributed to the Umayyad caliph al-Walid I, (Ṣanʿāʾ DAM 20-33.1)

These illuminations use ornamental motifs and pigments that have experienced variations over time and in space. For example, there is a set of manuscripts dating from the Umayyad era that employ architectural elements in their decorations.

Colophons and notes

The colophons in Qur’anic manuscripts are the final sections that provide details about the scribe, the completion date, the place where the manuscript was copied, and sometimes additional remarks. These colophons offer valuable information about the history, provenance, and individuals involved in the making of the manuscript.

Sometimes, manuscripts contain additional notes added at various locations within the page. The most common text is the act of donating the manuscript to a religious institution (waqf/ḥabs), which can be presented in different ways and be more or less comprehensive. But one can also find birth or death records, magic squares, commentaries, and so on.

Colophons and notes serve as essential sources for understanding the context, cultural aspects, and transmission of the Qur’an throughout history.

The Content

Consonantal skeleton (rasm in Arabic) and its variations

During the first centuries of the Hegira, the graphic system of Arabic underwent gradual transformations. The earliest dated witnesses indicate that one of the first reforms concerned the letter alif, which was gradually assigned the value of the long vowel /ā/. This reform is thought to have begun in Arabia in the pre-Umayyad period (C. J. Robin, “La réforme de l’écriture”). The notation of this long vowel /ā/ shows disparities in the Qur’anic manuscripts which could constitute relevant criteria in the identification of the manuscripts.

Orthographical variation of long vowel

Orthographical variation of long vowel

In addition to variations in long vowels, we occasionally observe variations in other consonants. Most of the time, these variations correspond to those that Islamic Tradition attributes to the regional codices (maṣāḥif al-amṣār); which are the copies that the third caliph ‘Uthmān b. ‘Affān is said to have sent to the various garrisons of the Islamic empire. Thus, by comparing the variants of the manuscripts with those recorded in tradition, it is possible to see whether the manuscript agrees with one of these regional codices in particular.

Apart from these alterations, other consonantal variations are sometimes noted, but these are much rarer in manuscripts, and it is difficult to determine whether these variations are significant or should be attributed to copying errors. With the exception of the Ṣanʿāʾ palimpsest where entire terms have been changed, the manuscripts we have explored so far faithfully adhere to the Uthmanic text as it is edited today.

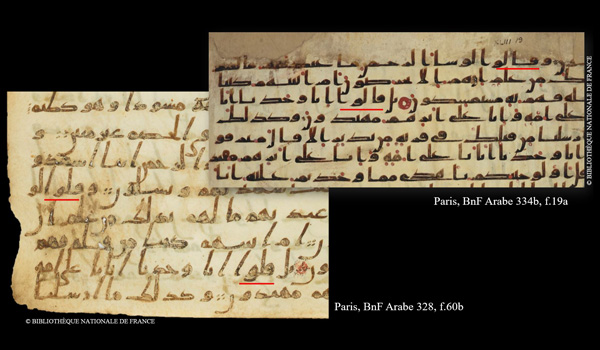

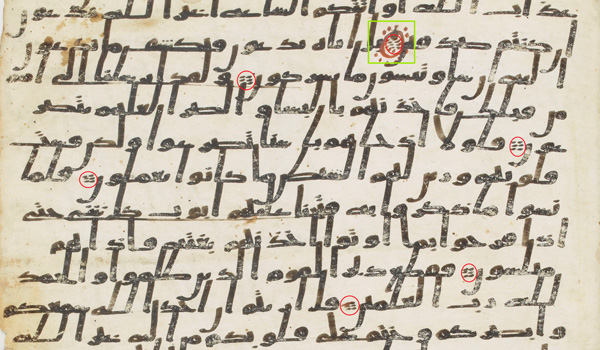

Diacritical signs

It is often said that the oldest manuscripts had no diacritical dots to distinguish the homograph consonants (ba, ta, tha, nun and ya’ for example). However, the Qur’anic manuscripts – like the inscriptions, graffiti and papyri dating from the 7th century – show that diacritical dots were indeed used from the outset, but not in a uniform and systematic way.

Some manuscripts contain very few: the muṣḥaf in the British Library (Or. 2165), for example, contains many ambiguous consonants (76%). Others, on the contrary, are almost completely dotted, removing any ambiguity when reading the text (see my article “Consonantal dotting in early Qur’anic manuscripts: A fully dotted Qur’an fragment from the AH. 1st/AD. 7th century”).

Paradoxically, there are much later manuscripts that are completely devoid of diacritics (e.g. muṣḥaf J1, Bibliothèque Nationale du Royaume du Maroc).

Absence of diacritical signs in a muṣḥaf from the 4th H./10th CE or 5th/11th century (J1, BNRM)

Absence of diacritical signs in a muṣḥaf from the 4th H./10th CE or 5th/11th century (J1, BNRM)

Furthermore, there are variations in the system itself. Even today in the Maghreb, the letter “fā'” is marked with a dot below it and the letter “qāf” with a dot above it, while in Middle Eastern countries, “fā'” carries a dot above it and “qāf” two dots above it. The origin of this variation dates back to the very first century of Islam (Kaplony, “What are those few dots for?”).

Vocalization

A large number of manuscripts dating from the first three Islamic centuries feature a vocalization system represented by colored dots. Dating this vocalization is relatively difficult, as it uses a colored ink, different from the text. It necessarily occurs after the copying of the text; however, the challenge lies in determining how much time elapses between the copying of the text and the vocalization.

It is assumed that the invention of the vocalization system occurred during the Umayyad period because many manuscripts datable from this period are vocalized, and this observation aligns with accounts from tradition that place it at the same time. However, as of now, no material evidence allows us to know more about the place or the actors involved in the reform.

Vowel dots

Vowel dots

This primitive vocalization system operates by using the position of the dot relative to the consonantal skeleton to indicate the vowel. Thus, a dot above a consonant indicates the sound /a/ (fatḥa), a dot to the left of the letter indicates the sound /u/ (ḍamma), and a dot below indicates the sound /i/ (kasra). It is worth noting that there are specific rules for indicating the glottal stop (hamza).

Furthermore, the color system – initially monochrome – gradually diversifies: other colors are used with different functions, again depending on the region. Contemporary scholars of these practices, such as Abū ʿAmr al-Dānī in Andalusia or Abū Ḥātim al-Sijistānī in Iran, allow us to locate these various traditions.

It is difficult to determine when modern vowels began to be used.

Textual Division into Verses

The division into verses is an almost systematic feature of series of ancient manuscripts. With the exception of some late series, datable to the 9th century, in which there is no division, the act of separating the verses is part of the initial copying program, just like the consonantal skeleton, and therefore constitutes an important element of manuscript transmission.

Verse Division

Verse Division

In the manuscripts, the division system sometimes diverge from the Vulgate on the location of certain verse endings. Some of these variations are found in Muslim scholarly literature from the 9th century CE, dedicated to the division of verses (fawāṣil) and its variations among several regional schools.

Textual division into groups of verses

Unlike verse divisions, the division into groups of five or ten verses does not belong to the earliest phase of transmission. It sometimes appears in ancient copies, but it was added later, often in red, above an original division.

The use of a different color from that of the text prevents any dating attempt; it cannot be known whether this element was added immediately after copying or if a period of time elapsed between the two operations.

Textual division into sections

The Qur’an is traditionally divided into several equal sections to facilitate its recitation and study. This division is not based on thematic content but rather serves as a practical means of navigating through the Qur’an. It helps in organizing recitation phases and facilitates memorization.

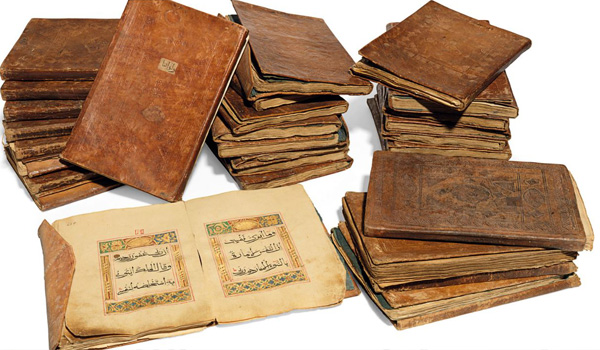

The most common division is into thirty sections, known as juz’ (plural: ajzā’). Each juz’ contains approximately one thirtieth of the content of the Qur’an, allowing readers to complete the entire Qur’an by reciting one section per day for thirty days. Another widely used division is into sixty ḥizb (plural: aḥzāb). However, there are many other divisions such as twenty-seven – corresponding to the 27 nights of Ramadan -, ten, nine, eight… down to the division into two halves. These divisions are sometimes mentioned in the margins (see my article “Regarding a Quranic manuscript in Kufic script given to the Great Mosque of Malaga”) or used to separate the content into several individual volumes.

Chinese Muṣḥaf divided into 30 volumes, 18th century

Chinese Muṣḥaf divided into 30 volumes, 18th century

The history of books: places of preservation

Over the centuries, Qur’anic manuscripts have been preserved in various places: some were part of the royal libraries of caliphs and sultans, while others belonged to the libraries of notables. The majority, however, was inalienable property (in Arabic: “waqf” or “ḥabs“) and deposited in places of worship such as mosques or mausoleums, and places of learning such as the madrasa.

At present, we can locate four main repositories (see below) that housed large collections of Qur’ans dating from the first three centuries of Islam. There are, of course, other manuscript repositories throughout the Islamic empire – from Morocco to India – but the number of ancient Qur’anic fragments is much smaller, and their journeys are often difficult to reconstruct.

The history and content of these main manuscript deposits are still largely unclear for several reasons.

Firstly, the collections were dispersed, in some cases considerably, sometimes by erudite bibliophiles, sometimes by unscrupulous dealers, resulting in a redistribution of the collections and a decontextualisation of the fragments.

In addition to the problem of dispersed holdings, work is considerably hampered by limited access to documentation. This is due, on the one hand, to the problematic conditions in which the manuscripts are kept – absence of a catalogue, critical state of conservation – and, on the other, to the limited number of publications devoted to Qur’anic manuscripts.

The four Genizah

The term “genizah” is generally used to describe these deposits of ancient Qur’anic manuscripts. Derived from Hebrew, the word ‘genizah’ refers to a storage place, usually within a synagogue or Jewish community, where documents, sacred texts or writings containing Hebrew script that are no longer in use or have reached a state of disrepair are deposited. The main reason for depositing these documents in a genizah is to show respect for the writings, particularly those containing the name of God.

The term ‘genizah’ is now used more widely to refer to any repository or storage place for discarded sacred texts or documents, emphasising the importance of showing respect for written documents containing sacred scripture.

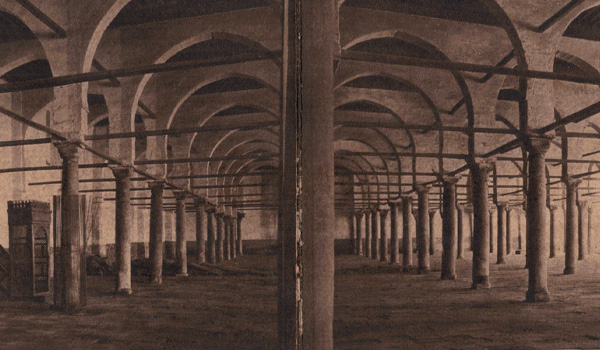

The Mosque of ‘Amr in Fusṭāṭ (Cairo)

The Great Mosque of ‘Amr ibn al-‘Āṣ in Fusṭāṭ, in Old Cairo, housed an important collection of manuscripts. The exact conditions of its preservation are not well known.

Some information is, however, provided by Orientalists, who visited the place, between the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century. They described the collection as ‘fragments piled up on the floor’, in a room in the mosque, or even hidden in an underground passage, according to Jean-Joseph Marcel. However, fragments from this collection had been circulating long before, among Eastern and Western bibliophiles.

The Great Mosque of ‘Amr ibn al-‘Āṣ in Fusṭāṭ

The Great Mosque of ‘Amr ibn al-‘Āṣ in Fusṭāṭ

Until the mid-20th century, the manuscripts of the ‘Amr Mosque supplied the collections of Western orientalists and antiquarians, leading to a massive dispersal of that collection. Today, the manuscripts are scattered among different collections.

The Great Mosque in Kairouan

A second collection of manuscripts can be found in Kairouan, today mainly in the Raqqāda Museum. It was discovered in 1896, in the maqṣūra of the Great Mosque of ‘Uqba ibn Nāfi’ (Muranyi, “Geniza or ḥubus”). Among the documents was an inventory of the collection, dated to the late 13th century CE, which listed 66 Qur’anic manuscripts preserved in situ at that time, if not slightly earlier.

The collection includes a number of manuscripts dating from the 9th century, but very few earlier ones.

The Great Mosque of ‘Uqba ibn Nāfi’ in Kairouan

The Great Mosque of ‘Uqba ibn Nāfi’ in Kairouan

The history of this library beyond the 9th century CE remains to be studied. The low number of earlier manuscripts suggests that it did not play a major role at that time. It is also possible that some of its manuscripts were brought back from Egypt, whose libraries were looted between the 10th and 11th centuries CE.

The Great Mosque of the Umayyads in Damascus

Between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, a large deposit of documents was discovered in the small octagonal chapel (qubbat al-khazna or bayt al-māl) in the courtyard of the Great Mosque, containing documents from various periods (from Late Antiquity to the modern era) in different languages (Greek, Syriac, Coptic, Armenian and Arabic). It must have housed manuscripts at least as early as 1874 or 1875 since the architect Jules Bourgoin, writing at the time, described it as a library.

The Great Mosque of the Umayyads in Damascus

The Great Mosque of the Umayyads in Damascus

During the second half of the 19th century, the Damascus collection experienced a situation similar to that of Fusṭāṭ. Several fragments were acquired by Europeans, evidence that the collection was known before the fire of 1893, or the visit of Bruno Violet in 1900. The collections of Charles Schefer (1820-1898), the Prussian consul Johann G. Wetzstein (1815-1905) and Edward H. Palmer (1840-1882) were built up at this time. These collections later became part of the holdings of public libraries: the first at the Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, the second at German libraries (Tübingen and the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin), and the last at the Cambridge University Library.

The Ottoman authorities then decided to transfer the collection to Istanbul, perhaps to prevent it from suffering the same fate as that of Fusṭāṭ. According to F. Déroche, a few well-preserved volumes were kept in the library of the Topkapi Palace Museum, while the more fragmentary folios were transferred to the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts (Şam Evrak collection). This collection contains hundreds of thousands of fragments of folios that have so far only been summarily inventoried. A few other Qur’anic fragments remain in the National Museum in Damascus (D’Ottone, “Manuscripts as Mirrors”).

The Great Mosque of Ṣanʿāʾ

In 1973, the restoration of the ceiling of the Great Mosque uncovered a large number of fragments of documents, including Qur’anic fragments, stored in the space between the ceiling and the roof. The presence of a few printed documents suggests a recent deposit, probably during a previous restoration of the mosque’s library (Costa, “La Moschea grande”).

The Ṣanʿāʾ Great Mosque

The Ṣanʿāʾ Great Mosque

The statistics provided by the German team which restored and classified the collection are unclear. In the 1980s, Gerd-Rüdiger Puin and Hans-Caspar Graf von Bothmer mentioned 40,000 fragments belonging to more than 1,000 Qur’anic codices. Among them, they mention 700 or 750 Qur’ans on parchment. In 1987, von Bothmer also mentioned 22 manuscripts in hijāzī script. But in 1996, Puin reported 900 Qur’ans on parchment, 10% of which they said were in “pre-cufic, hijāzī or mā’il” script. These fragments include a unique document: a Qur’anic palimpsest whose scriptio inferior diverges from the official Vulgate. The whole remained in-situ, preserved in the House of Manuscripts (Dār al-makhṭūṭāt).

Manuscripts outside the genizahs

Independently of these four collections, other ancient manuscripts circulated. Among these, several have been attributed, a posteriori, to eminent figures, such as the caliph ‘Uthmān ibn ‘Affān (r. 644 to 656) or Imam ‘Alī ibn Abī Ṭālib (r. 656 to 661).

For some of them, textual sources allow us to reconstruct their path. One of them is the Mushaf in Sayyida Zaynab Mosque in Cairo which is identified as the copy kept in the madrasa al-Faḍiliyya, at least since the Ayyubid period (Munajjid, Dirāsāt fī ta’rīkh al-khaṭṭ).

Another manuscript, also attributed to ‘Uthmān, was in the Prophet’s mosque in Medina at the time Ibn Jubayr (d. 1217) visited it. It is probably this same manuscript that is mentioned by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919: “the original Koran having belonged to the Caliph Osman and removed from Medina by the Turkish authorities to be offered to the former Emperor Wilhelm II” (Marx, “Le Coran de ‘Uthmān”). What happened to this manuscript? It is certainly the manuscript that G. Bergsträsser photographed in Topkapi Palace Library in Istanbul in the 1920s. A facsimile of this manuscript was recently published by T. Altikulaç, Muṣḥaf- I Şerîf (Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi Kütüphanesi, Medine nr. 1), 2020, Volumes I and II, Istanbul :IRCICA.

Unfortunately, these peregrinations are not systematically recorded by history. For a great majority of the manuscripts, information about the provenance is unclear.

This is notably the case for this other muṣḥaf attributed to the caliph ‘Uthmān kept in the Hast-Imam library in Tashkent in Uzbekistan about which there were two local narratives regarding its provenance: either from the library of the Ottoman sultan Bayezid I (r. 1389-1402), or from Tamerlane’s Library (see my article about this manuscript: “The Samarkand Qurʿān”, forthcoming in The History and Development of the Arabic Script, King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies, Riyadh).

The study of these manuscripts from parallel paths remains to be done.

There are a large number of public and private libraries and museums today preserving Qur’anic manuscripts that are waiting to be restored, digitised and studied. These deposits are scattered throughout the Islamic world, from libraries in Morocco, such as that of the Qarawiyyin Mosque in Fez, to those in Indonesia. Were the manuscripts found there copied locally or did they come from elsewhere? We will need to study them in more detail to answer this question.

The history of the collections sheds light on the socio-cultural context in which the muṣḥaf, the Qur’anic book, developed. These large collections that we now call “genizah” probably once constituted libraries, in which manuscripts of the Qur’an were visibly used, for several decades or more, by the community. Many have preserved traces of reading traditions, correction protocols, division into sections or even indications of prostration for the purposes of worship.

The functionality of these libraries also justifies the fact that no preserved text deviates significantly from the ‘Uthmānic Vulgate. Yet the discovery of the Ṣanʿāʾ palimpsest, in which the original text was deliberately erased, bears witness to the fact that other versions of the text existed. It should be pointed out that the formal presentation of the original text – its format, handwriting, layout – does not diverge in any way from what is known elsewhere.

Can the material available today be representative of the transmission of the Qur’an?

The existence of manuscripts circulating outside the collections raises the question of lost libraries, particularly in Iraq and Arabia, two centres that were important in the transmission of the Qur’anic text.

Maybe new Qur’anic libraries will come to light in the future, and that new material will lead us to review the history of manuscript transmission. Among this material, it is possible that other palimpsests will be discovered, with other variants of the Qur’anic text. The hope is small, however, given the intense standardisation activity that took place over the first three centuries.